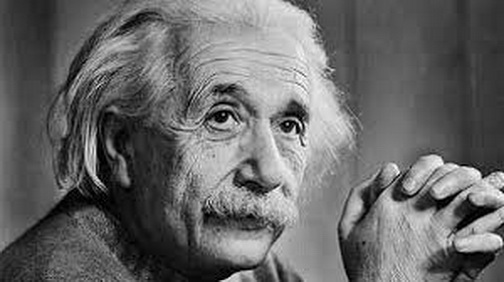

In the summer of 1939 Albert Einstein was on holiday in a small resort town on the tip of Long Island. His peaceful summer, however, was about to be shattered by a visit from an old friend and colleague from his years in Berlin. The visitor was the physicist Leo Szilard. He had come to tell Einstein that he feared the Nazis could soon be in possession of a terrible new weapon and that something had to be done.

Szilard believed that recent scientific breakthroughs meant it was now possible to convert mass into energy. And that this could be used to make a bomb. If this were to happen, it would be a terrible realisation of the law of nature Einstein had discovered some 34 years earlier. September 1905 was Einstein’s ‘miracle year’. While working as a patents clerk in the Swiss capital Berne Einstein submitted a three-page supplement to his special theory of relativity, published earlier that year. In those pages he derived the most famous equation of all time; e=mc², energy is equal to mass multiplied by the speed of light squared.

The equation showed that mass and energy were related and that one could, in theory, be transformed into the other. But because the speed of light squared is such a huge number, it meant that even a small amount of mass could potentially be converted into a huge amount of energy. Ever since the discovery of radioactivity in the late 19th century, scientists had realised that the atomic nucleus could contain a large amount of energy. Einstein’s revolutionary equation showed them, for the first time, just how much there was.